A Complete Guide to Moonshine, Still Plans, Home Distilling and Moonshining

The manufacture of moonshine illicit whiskey in the mountains is not dead. Far from it. As long as the operation of a still remains so financially rewarding, it will never die.

There will always be men ready to take their chances against the law for such an attractive profit, and willing to take their punishment when they are caught.

Background to Moonshine Making:

Moonshining Making is a fine art, however, effectively disappeared some time ago.

There were several reasons. One was the age of aspirin and modern medicine. As home doctoring lost its stature, the demand for pure corn whiskey as an essential ingredient of many home remedies vanished along with those remedies. Increasing affluence was another reason. Young people, rather than follow in their parents' footsteps, decided that there were easier ways to make money; and they were right.

Third, and perhaps most influential of all, was the arrival, even in moonshining, of that peculiarly human disease known to most of us as greed. One fateful night, some force whispered in an unsuspecting moonshiner's ear, "Look. Add this gadget to your still and you'll double your production. Double your production, and you can double your profits."

Soon the small operators were being forced out of business, and moonshining, like most other manufacturing enterprises, was quickly taken over by a breed of men bent on making money—and lots of it. Loss of pride in the product, and loss of time taken with the product increased in direct proportion to the desire for production; and thus moonshining as a fine art was buried in a quiet little ceremony attended only by those mourners who had once been the proud artists, known far and wide across the hills for the excellence of their product.

Too old to continue making it themselves, and with no one following behind them, they were reduced to reminiscing about "the good old days when the whiskey that was made was really whiskey, and no questions asked." We got interested in the subject one day when, far back in the hills whose streams build the Little Tennessee, we found the remains of a small stone furnace and a wooden box and barrel.

On describing the location to several people, we were amazed to discover that they all knew whose still it had been. They all affirmed that from that still had come some of the "finest home brew these mountains ever saw. Nobody makes it like that any more," they said.

Suddenly moonshining fell into the same category as faith healing, planting by the signs, and all the other vanishing customs that were a part of a rugged, self-sufficient culture that is now disappearing.

Our job being to record these things before they die, we tackled moonshining too. In the six months that followed, we interviewed close to a hundred people. Sheriffs, federal men, lawyers, retired practitioners of the old art, haulers, distributors, and men who make it today for a living; all became subjects for our questioning.

Many were extremely reluctant to talk, but as our information slowly increased we were able to use it as a lever—"Here's what we know so far. What can you add?"

Finally we gained their faith, and they opened up. We promised not to print or reveal the names of those who wished to remain anonymous. They knew in advance, however, that we intended to print the information we gathered—all except that which we were specifically asked not to reveal. And here it is.

The History of Moonshine - In the Beginning

According to Horace Kephart in Our Southern Highlanders (Macmillan, 1914), the story really begins with the traditional hatred of Britons for excise taxes. As an example, he quotes the poet Burns' response to an impost levied by the town of Edinburgh.Thae curst horse-leeches o' the Excise

Especially hated were those laws which struck at the national drink which families had made in their own small stills for hundreds of years. Kephart explains that one of the reasons for the hatred of the excise officers was the fact that they were empowered by law to enter private houses and search at their own discretion.

As the laws got harsher, so too the amount of rebellion and the amount of under-the-table cooperation between local officials and the moonshiners. Kephart quotes a historian of that time:

Not infrequently the gauger could have laid his hands upon a dozen stills within as many hours; but he had cogent reasons for avoiding discoveries unless absolutely forced to make them. [This over two hundred years ago.]

A hatred of the excise collectors was especially pronounced in Ireland where tiny stills dotted rocky mountain coves in true moonshining tradition. Kephart quotes the same historian:

The very name [gauger, or government official] invariably aroused the worst passions. To kill a gauger was considered anything but a crime; wherever it could be done with comparative safety, he was hunted to death.

Scotchmen (now known as Scotch-Irish) exported to the three northern counties of Ireland quickly learned from the Irish how to make and defend stills.

When they fell out with the British government, great numbers of them emigrated to western Pennsylvania and into the Appalachian Mountains which they opened up for our civilization. They brought with them, of course, their hatred of excise and their knowledge of moonshining, in effect transplanting it to America by the mid 1700s. Many of the mountaineers today are direct descendants of this stock.

These Scotch-Irish frontiersmen would hardly be called dishonorable people. In fact, they were Washington's favorite troops as the First Regiment of Foot of the Continental Army. Trouble began after Independence, however, with Hamilton's first excise tax in 1791.

Whiskey was one of the few sources of cash income the mountaineers had for buying such goods as sugar, calico, and gunpowder from the pack trains which came through periodically. Excise taxes wiped out most of the cash profit. Kephart quotes Albert Gallatin:

We have no means of bringing the produce of our lands to sale either in grain or meal. We are therefore distillers through necessity, not choice, that we may comprehend the greatest value in the smallest size and weight.

The same argument persists even today—battles raged around it through the Whiskey Insurrection of 1794, and over government taxes levied during the Civil War, Prohibition, and so on right to this moment.

The History of Moonshining - The Law vs. The Blockader

The reasons for the continuous feud implied in this heading should be obvious by now. The government is losing money that it feels rightfully belongs to it. This has always been the case. In the report from the Commissioner of Internal Revenue for 1877-78, the following appeared:In [the southern Appalachian states from West Virginia through Georgia and including Alabama] there are known to exist 5,000 copper stills.

It's different now? Clearly not, as seen in an article in the May 3,1968 Atlanta Constitution on the interim report of the Governor's Crime Commission. In October, 1967, there were around 750 illicit stills in Georgia, operating at a mash capacity of over 750,000 gallons.

This amounts to approximately $52 million in annual federal excise tax fraud, and almost $19 million in state fraud. The article quotes the Commission, placing the blame for Georgia's ranking as the leading producer of moonshine in the United States on "corrupt officials, a misinformed and sometimes uninterested public, and the climate created by Georgia's 129 dry counties."

Originally arrests had been made by government officials ("Feds" or "Revenuers"), but during Prohibition much of the enforcement was left up to the local sheriffs. This put many of them in a peculiar position, for the moonshiners they were being told to arrest were, in many cases, people they had known all their lives.

As it turned out, however, most of the lawbreakers were reserving their hostility for the federal agents and the volunteers (called "Revenue Dogs") who helped them. They had nothing against their sheriff friends who, they understood, were simply doing their jobs.

The sheriffs, for their part, understood the economic plight of the moonshiners. For many of these people, making moonshine was the only way they had at the time of feeding their families. As one told us, "I felt like I was making an honest dollar, and if it hadn't a been for that stuff, we'd a had an empty table around here."

The situation resulted in a strange, friendly rivalry in most cases. As one moonshiner said, "I never gave an officer trouble except catchin' me. After I'uz caught, I'uz his pickaninny."

The same man told us of a time when he was caught by a local official who was as friendly a man as he had ever met. He wasn't treated like a criminal or an animal, but treated with respect as another man making a living for a large family—which he was. After it was all over, the local official had made'a friend instead of an enemy, and the two are still fast friends today.

During the same period of time, there was another sheriff whom he often encountered on the streets of a little town in North Carolina. The sheriff would always come up to him, greet him, and ask him what he was up to down in Georgia. The other would usually reply, "Oh, not much goin' on down there."

We talked to several retired sheriffs (one of whom, Luther Rickman, was the first sheriff to raid a still in Rabun County), and they agreed completely. Most of the blockaders that they had encountered ran small operations, and the whiskey they made was in the best traditions of cleanliness. Besides, times were hard, and a man had to eat.

Despite the fact that the sheriffs at that time were paid on the "fee system," and thus their entire salary depended on the number of arrests they made, they did not go out looking for stills. They made arrests only after reports had been turned in voluntarily by informers who, as we shall see later, usually had personal reasons for reporting the stills. They were never hired to do so.

Operating on the fee system, the local officials got $10 just for still. If they were able to catch the operator also, they received between $40 and $60. Extra money was given them if they brought in witnesses who could help convict. For the blockader's car, they received approximately half the price the blockader had to pay to get it back which was usually the cash value of the car. And they were allowed to keep any money they could get from selling the copper out of which the still had been made.

Confiscated moonshine, beer, and the like were poured out. The sugar was often donated to an institution like a school or hospital. The number of stills actually uncovered varied drastically from month to month. Some months, twenty or thirty would be caught and "cut down," but other months, none at all would be discovered.

Hardest of all was catching the men actually making a run. In almost all cases they had lookouts who were armed with bells, horns, or rifles, and who invariably sounded the alarm at the first sign of danger. By the time the sheriff could get to the still, the men would have all fled into the surrounding hills. We were told about one man who was paid a hundred dollars a week just as a sentry. Another still was guarded by the operator's wife who simply sat in her home with a walkie-talkie that connected her with her husband while he was working.

The moonshine still, which sat against a cliff behind the house, could only be reached by one route, and that route passed directly in front of the house. The operator was never caught at work. On those occasions when the sheriffs did manage to catch the men red-handed, they usually resigned themselves to the fact that they had been caught by a better man, and wound up laughing about it.

On one raid, a sheriff caught four men single-handedly. There was no struggle. They helped the official cut their still apart; and when the job was done, everyone sat down and had lunch together. When they had finished, the sheriff told the men to come down to the courthouse within the next few days and post bond, and then he left.

The same sheriff told us that only rarely did he bring a man in. He almost always told them to show up at their convenience, and they always did. To run would simply have shown their lack of honor and integrity, and they would have ultimately lost face with their community and their customers. They simply paid their fines like men, and went on about their business.

It was a rivalry that often led to friendships that are maintained today. One of the sheriffs, for example, spent two evenings introducing us to retired moonshiners, some of whom he had arrested himself. It was obvious that they bore no grudges, and we spent some of the most entertaining evenings listening to a blockader tell a sheriff about the times he got away, and how; and naturally, about the times when he was not so lucky.

Today federal agents have largely taken over again, and so the character of the struggle has changed. The agents actively stalk their quarry, sometimes even resorting to light planes in which they fly over the hills, always watching. In the opinion of some people, this is just as it should be.

One said, "The operations are so much bigger now, and sloppier. If the Feds can't get'em, the Pure Food and Drugs ought to try. That stuff they're makin' now'll kill a man." And another said, "People used to take great pride in their work, but the pride has left and the dollar's come in, by th' way."

We was stillin' one day away up on a side of a hill away from everything, mindin' our own business, just gettin' ready t'make a run when my partner all of a sudden sees somethin' move in a pasture one hill over. Couldn't tell who he was. Too far away. I couldn't see him at all, stuck away behind a fence post like that.

We went on workin', keepin' one eye out, and after we was through, and whatever that was over yonder had gone on, we went over to see. It was somebody there all right. I seed that checkedy sole print in th' soft ground and we moved her out that night. It was a revenuer all right. I know because I ran into him again later and he asked me about it. But know how I knew before that? Because of that boot print, and because he didn't come down and say hello. A friend of ours would have.

Moonshining - Hiding the Moonshine Still

Since the days of excise, moonshiners have been forced to hide their stills. Here are some of the ways they have used.1. Since cold running water is an absolute necessity, stills are often high up on the side of a mountain near the source of a stream. Water on the north side of a hill flowing west was preferred by many. Some count on the inaccessibility of the spot they chose for protection.

Others, however: build a log shed over the still and cover this with evergreen branches bend living saplings over so they conceal the still.

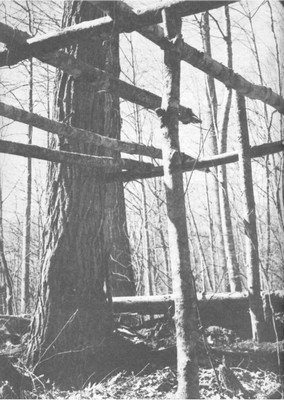

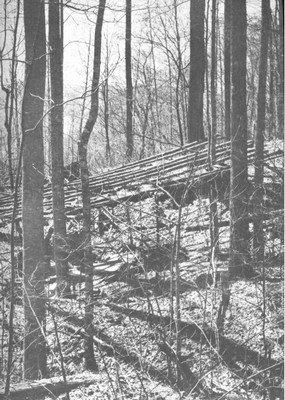

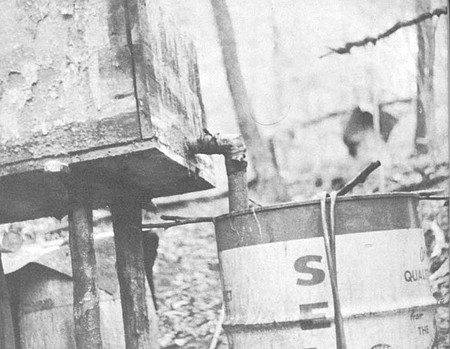

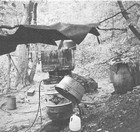

Hiding the moonshine still under branches.This log framework was built in the woods to conceal a still. When finished, it was covered with branches.

A huge still operated under this shed for over a year before it

was discovered and cut down by federal officers.

They should be arranged so that they blend in with the landscape; find a cave and cover up the front of it; find a large laurel thicket, crawl into the center of it, and cut and out a room right in the middle of the thicket big enough for the still; find a large spruce and put the still under its branches so it can't be seen from a plane.

2. The legend has grown that all one has to do to find a still is follow a likely looking branch up into a cove and then poke around until uncovering something suspicious. Moonshiners have countered by locating many stills in so-called "dry hollows."

They find a cove that has no stream and pipe in the water they need from a higher, "wet" cove. Using all the hiding devices mentioned above, they: buy two-inch piping, and run the pipe underground, around a ridge and into the dry hollow; get plastic pipe and run it under leaves, or in a trench; forget about the cove, and put the still right out on the top of a dry ridge, or in a laurel thicket, and pipe the water from a higher source.

3. Other moonshiners get far more elaborate and actually dig out an underground room big enough to stand in comfortably. Rows of beams are set in overhead, covered with dirt, and plant materials are actually planted overhead. A small trapdoor in the center of the roof, also covered with a growth, lifts up, exposing a ladder which goes down into the room. A vent pipe, cleverly concealed, carries off fumes. Some rooms are even wired for electricity.

4. Another way to avoid detection is by moving constantly. Some men follow logging jobs, figuring that the loggers will destroy all signs of their moonshining activities. In fact, loggers themselves often run stills in conjunction with their logging job.

5. Some men set up in a site the revenuers have just cut down believing that they won't be back for at least two months unless they get another report of activity there.

6. Others place their stills right in existing buildings that are not often visited, or would not normally be suspected—barns, silos, smokehouses, tool sheds, abandoned homes or buildings, even the basements of their own homes. Others run right in the center of town behind a false-fronted store or in a condemned building.

7. One man we know, believing that the revenuers will be looking for his still to be concealed, has it right out in the open, near the main highway, with only a few trees in front. He hasn't been caught yet.

8. Smoke, too, is a problem, but only at the beginning of the run. When the fire begins burning well, it gives off heat waves rather than smoke. Thus, often the fire is started just before dawn and is burning well enough by daylight to escape detection.

Others, however, worried about smoke, "burn their smoke." A worm or pipe which runs out the side of the furnace and back into the firebox recirculates the smoke and makes it invisible.

We also have heard of a man who somehow piped his smoke so that it came up underwater—this supposedly dispersed it so effectively that it could not be seen. Others counted on the leaves and branches over their shelters to disperse the smoke. Now any conceivable problem of smoke has been wiped out with the use of fuels such as butane or kerosene.

9. A dead giveaway as to the location of a still is a "sign" or trace of activity. Moonshiners constantly guard against this. An empty sugar bag, the lid from a fruit jar, a piece of copper—all can reveal their location.

An even bigger problem is that of trails. There are various ways if the still is in the woods, always enter the woods from the road at a different point. Then, one hundred fifty yards up the hill, cross over to the main trail which begins as many yards or so off the road. enter stills that are in a cove or hollow from the ridge above the still, instead of coming uphill from the front.

One man who lives at the base of a high ridge said he could sit on his porch on a summer night and sometimes hear the voices of men, on the way to their still, shouting at the mules that were carrying in the supplies. If he looked carefully, he could see their lanterns winking high up on the ridge as they came in the back way to keep from being caught. And locate the still on a stream that runs into a lake, through brush, and far away from any road.

They always enter the still at night, by boat. find a cut in the road the top of which is capped with a rock ledge, and is either level with or a little higher than a pickup truck bed.

Load or unload from this rock to prevent leaving trails. use fuel like butane gas to prevent leaving signs such as stumps of trees and wood chips and clipped off foliage.

Once a man was caught selling whiskey. He had painted some of the jars to look as though they contained buttermilk, but then he ran out of paint and had to use clear jars for the rest of his supply. When the revenuers caught him, they confiscated the clear jars; but so convincingly were the others painted that they did not even bother to open them. They simply left them behind, and the salesman was able to clear a profit, despite the loss of part of his wares.

Moonshining - Finding the Hidden Moonshine Still

Law officers have used many methods for finding hidden stills.Each time one became popular, the blockaders countered by hiding it in a different way. Here, however, are some of the methods used.1. They are always alert for signs. A brick dropped in the middle of the woods is an obvious one. Why would it be there except for a furnace? Spilled meal or sugar on the side of a road is suspicious.

A ladder left at the top of a high cut in the road is an obvious signal; probably it is used to load and unload supplies from the back of a pickup. Other signs include an empty sugar bag, a broken jar, a place in the woods where trees have been cut, a pile of charcoal, an empty cement bag, a broken shovel handle, a barrel stave, a burlap sack.

2. With an officer on either side of a backwoods dirt road—each two hundred yards away from the road, walking parallel to it—they search for a place where a trail begins.

3. With a boat, they search the edges of a lake. They look for signs of activity near a place where a branch empties into the lake. Such signs might be places where a boat has been pulled up on shore or slick trails made by dragging heavy feed bags.

4. They stake out a road and watch for signs of unusual activity in the early morning hours. They follow any cars heading up little used roads. Or an officer might stake out a section of woods and listen for sounds such as a hammer against metal, the sound of a thump barrel, etc.

5. Usually areas where moonshine is being made have a distinctive smell. Law officers may detect that while walking through forest. Many stills are found by people like hunters who spend much time in the woods and merely stumble across one by accident.

Others are found by searching small branches that flow from hillsides through heavy growth. The most prevalent means of finding stills, however, remains the informer.

Often, they are people with a grudge or an axe to grind. One moonshiner characterized them as people, "who don't have enough of their own business to mind, and so they feel obligated to mind th' business of other people. Th' lowest man I know," he continued, "is one who wins your confidence, buys your liquor, and then turns you in. I believe there's a special place for people like that after they die." Some informers hardly deserve such criticism.

A mother whose young son comes in drunk and inadvertently tells her where he got the whiskey might well try to do something about it. A man who finds a blockader operating on his property without his permission a right to ask the sheriff to remove him. A more common motive, however, is jealousy.

Sheriffs told us story after story in which a man whose still had just been cut down would turn in another out of spite. "They've cut mine. I'll fix it so they'll get some others too. If I can't be running, I don't want them running either."

Another ex-sheriff told us the following story. "While I was in office, a man who owned a still invited a neighbor to come in with him and make a run of apple brandy. When the run was finished, they ended up with thirty-nine gallons. The owner of the still took twenty, and gave his neighbor nineteen. The more the neighbor thought about it, the madder he got. What really irked him was that the owner of the still already had a buyer for his twenty gallons; he had none.

"They took their brandy and hid it in separate places. That night, the neighbor came to me and told me that he knew where twenty gallons of fresh brandy was hidden and wanted me to do something bout it. So I got out of bed and went and poured the brandy out, like I'm supposed to do. "

Later I found out that when the buyer came to get his twenty gallons, the neighbor stopped him, told him that the sheriff had already found it and poured it out, and then sold him his nineteen. I found out all about it from the owner of the still who came in here as mad as any man I ever saw. I just did keep him from going and killing that neighbor."

Sometimes the stories take surreal twists. The same officer also told us this story, and swore that it really happened. "

A man that lived around here while I was in office knew of an underground still that was a beautiful thing to look at. He wanted the rig himself, so one night he broke the lock on the trap door, got into the underground room, and took it.

The next day he came to me saying he knew where a still was that I should cut down, and he'd even come with me to show me where it was. I was suspicious, but I went. "When we got there, I saw right away that the lock on the door was broken, and when I got inside, I saw that the still was gone too. Well, I broke up what was left in there and then came back out and told the man that the still wasn't there.

"He really carried on when I said that, but I knew right away what was up. He had taken it, and wanted me to bust up the place so that the owner would think that / had gotten his still during my raid.

"I went back to the office, and not too long after that, the owner showed up and asked if I had gotten his still. When I told him I hadn't, he wanted to know who had stolen it. I knew all the time, but I never said anything. I never once let anyone know who I had gotten information from. It just would have caused trouble.

"Finally the man who owned it asked me if I would just keep my eyes open for it. He didn't want it back necessarily—just wanted to know when it showed up out of curiosity. Then he told me how he had dropped it one day and broken a piece of the collar. Said he had put a "V"-Shaped patch on the broken place, and that's how I'd know it was his.

"Well, I found out later that the man who had taken it in the first place had taken it home and put it in the loft of his barn. Two boys working for him loading hay found it up there, and they stole it from him.

"Several days later, there was a robbery in town, and that night I was in there looking around to see if I could pick up a clue or something. Just keeping my eyes open. While I was in there, these two boys came along. I got back out of the way out of sight, and these two sat down on some steps not far from me. I could hear everything they were saying. Turns out they were still laughing about this new still they had gotten and wondering where they could set it up and when they could get it running. You won't believe this, but they finally decided to set it up on a vacant piece of land that I owned—said I'd never look for it there in a hundred years. They'd make four or five runs and then they'd move it somewhere else.

"The next day I went up on the land where the boys had talked about setting it up—in some laurels up there—and sure enough, there it was, and there was the patch. I got it and took it into town to the office.

"When I saw the original owner again, I called him over. Said I had something to show him. Boys, his eyes popped right out of his head. That was it all right. I didn't tell him how I got it, but we had many a good laugh over that later on."

The fact that hogs love the corn mash that whiskey is made out of is legend. Often moonshiners were forced to put fences around their stills to keep hogs, who were kept on "open range" then, from falling into the mash boxes and drowning.

Once a two hundred-pound sow fell into a mash box where she drowned. The men running the still found her body in there several days later, but went on and made whiskey from the same mash anyway. From then on, if whiskey was too strong, the man drinking it would say, "That must'a had a dead hog in it."

Moonshining Glossary of Moonshine Still Parts and Equipment

Cap—the top third of the moonshine still. It is removable so that the still can be filled after a run.

Cap Arm—the copper pipe connecting the cap with the next section of the still; it conveys steam to this section.

Cape—the bulge in the main body of the moonshine still. It is the point of greatest circumference.

Collar—the connection for the cap and the body of the still.

Condenser—a two-walled, sealed pipe which is submerged in water. Steam forced into the top condenses and flows out the bottom.

Flake Stand—the container through which water is constantly flowing for final condensation of the steam. Holds the worm, condenser, or radiator, depending on which apparatus is being used.

Funnel—usually holds whatever material you are using to strain the whiskey. Whiskey passes through it and into the jug or jar.

Furnace—stone structure in which the still sits for heating.

Headache Stick—the long thump rod.

Heater Box (or pre-heater)—a device which heats the fresh beer which will be used in the next run.

Long Thump Rod—an open-ended copper pipe which conveys the steam into the bottom of the thump barrel where it is released.

Mash Stick—the stick used to break up the cap that forms over the mash and stir up the contents of the barrel. Sometimes it is made of a stick which has a crook in the end. Several holes are drilled in this crook, and pegs are inserted to form a comb-like device. It can also be a stick with several nails driven in the side.

Plug Stick—a hickory or white oak stick with a bundle of rags fastened to one end. The rags jam into the slop arm thus sealing the bottom of the still.

Proof Vial—a glass tube used to check the bead of the whiskey. A Bateman Drop bottle was the most popular as it held exactly one ounce, and was just the right shape. Others used now are bottles that rye flavoring comes in, or a government gauge.

Relay Arm—the pipe connection from the bottom of the relay barrel back into the still.

Relay Barrel or Dry Barrel—a fifty-gallon barrel with connections for the cap arm, relay arm, and a long thump rod. Catches "puke" from the still during boiling and conveys it back into the moonshine still.

Still—the container into which the beer is placed for boiling. Also called the Evaporator, Boiler, Kettle, or Cooker. The name can also refer to the entire operation from the evaporator through the flake stand.

Swab Stick or Toothbrush—a hickory stick half as thick as your arm and long enough to reach from the top to the bottom of the still. One end is beaten up well so that it frazzles and makes a fibrous swab. This is used to stir the beer in the still while waiting for it to come to a boil, thus preventing it from sticking to the sides of the still, or settling to the bottom and burning. If the latter happens, the whiskey will have a scorched taste.

Thump Barrel—also Thumper or Thump-Post—a barrel which holds fresh beer, and through which steam from the still bubbles thus doubling its strength. The strengthened steam moves from here into the short thump rod which carries it either into the heater box, or into the flake stand.

Worm—a copper tube, usually sixteen to twenty feet long which is coiled up so that it stands about two feet high and fits inside a barrel. Water flows around it for condensing the steam which passes into it from the still.

A Glossary of Some of the Expressions and Terms used in Distilling

Backings—also singlings and low-wines—what results after beer is run through a thumperless operation once. They have a good percentage of alcohol, but they won't hold a bead.Beer—the fermented liquid made from corn meal bases which, when cooked in the still, produces the moonshine.

Blockaders—men who made moonshine. The name is a holdover from the days in our history when blockades were common, as were blockade runners. Also gave rise to the expression "blockade whiskey." Blubber—the bubbles which result when moonshine in the proof vial is shaken violently.

Breaks at the Worm—an expression used at the moment when the whiskey coming out of the flake stand turns less than 100% proof, and thus will no longer hold a bead.

Dead Devils—tiny beads in the proof vial which indicate that the whiskey has been proofed sufficiently. Stop adding water or backings at the moment shaking the proof vial produces dead devils. Dog heads—when the beer is almost ready to run, it will boil up of its own accord in huge, convulsive bubbles which follow each other one at a time.

Doubled and Twisted—in the old stills, all the singlings were saved and then run through at the same time thus doubling their strength. Whiskey made in this fashion was called doubled and twisted. aints—dead beer; or backings that steam has been run through in a thumper to strengthen a run. These are drained and replaced before each new run.

Goose Eye—a good bead that holds a long time in the vial. High Shots—untempered, unproofed whiskey. At times it is nearly as strong as 200 proof.

Malt—corn meal made from grinding sprouted corn kernels. It is added to the barrels of mash to make the beer.

Mash—corn meal made from grinding unsprouted corn kernels. It is put in the barrels, mixed with water, allowed to work until it is a suitable base for the addition of the malt.

Pot-tail—see Slop.

Proof—see Temper.

A Run—an expression meaning to run the contents of the still through the whole operation once. It gave rise to expressions like, "There's gonna be a runnin' tomorrow," "He'll make us a run," etc.

Singlings—see Backings.

Slop—that which is left in the still after the whiskey will no longer hold a bead at the end of the worm. It is too weak to produce and so it is dumped at once. Left in the still, it will bum. Some people use it for hog feed, others in mash.

Sour Mash—mash made with pot-tail.

Sweet Mash—mash that has been made with pure water. The first run through the still is made with sweet mash.

Split Brandy—a mixture that is half whiskey, half brandy. It is made by mixing mash that is one-quarter fruit content. Then proceed as usual with the beer-making, and running.

Temper—the process of adding water or backings to the whiskey to reduce its strength to about 100% proof.

Various names are given to moonshine include ruckus juice (pronounced "rookus"), conversation fluid, corn squeezin's, corn, white, white lightening cove juice, thump whiskey, headache whiskey, blockade whiskey, etc. "Busthead" and "popskull" are names applied to whiskey which produces violent headaches due to various elements which have not been removed during the stilling process.

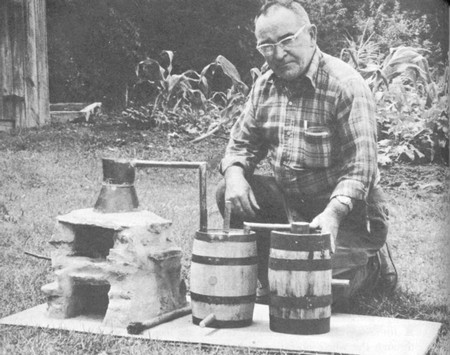

Buck

Carver kneels behind a one-gallon still he made for the

Foxfire museum.

The moonshine still is authentic in every detail from the flue of the

furnace to the tin-locked copper joints in the cooker and condenser to

the chestnut barrels Bill Lamb made for the model.

How to Build a Moonshine Still with Plans

First find the proper location for the operation. The next step is the construction of the furnace. The following pages include diagrams and photographs of two furnace styles which were extremely popular during the days of Prohibition. Only a few of them are seen today.The fuel used was almost always a hard wood such as oak or hickory. Ten- and twelve-foot logs would be fed into the bottom of the furnace with their ends sticking out in front. The fire was started, and as the logs burned, they were slowly fed into the furnace. Since the furnace was made to burn wood, the firebox was spacious.

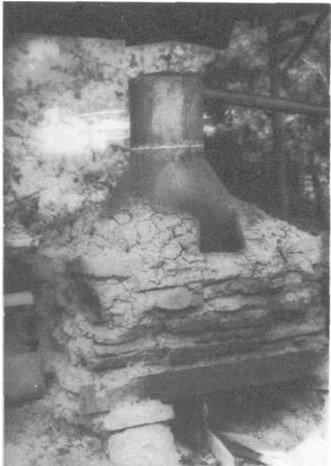

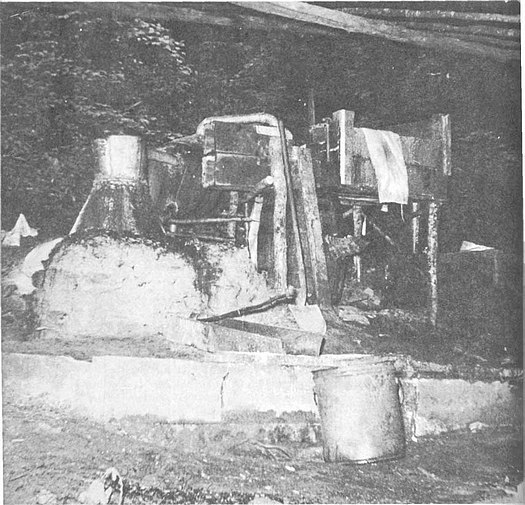

(Plate

263) A moonshine furnace made of rock and red clay. A

fire has been started in the firebox, the cap has been sealed on with

rye paste, and the operation is ready to go.

A bedrock

platform above the firebox kept the bottom of the

still from ever coming in direct contact with the fire. This

prevented the contents of the still from burning or becoming

scorched.

All heating took place around the sides of the still in an area that was completely enclosed except for the flue. The sides of the furnace touched the still at only one point, and that was above the cape at the point where the sides of the furnace tapered in to seal flush against the top half of the still (Plate 265). This area had to be sealed tightly to prevent heat escaping from below.

The flue was most carefully constructed for maximum draw. One man told us of a furnace he had built in which the draft was so strong that it would "draw out a torch." Natural stone was used, chinked with red clay. The first furnace illustrated is the "return" or "blockade" variety (Plate 264). The second is called the "groundhog" (Plate 266).

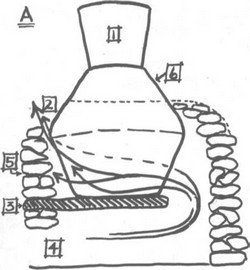

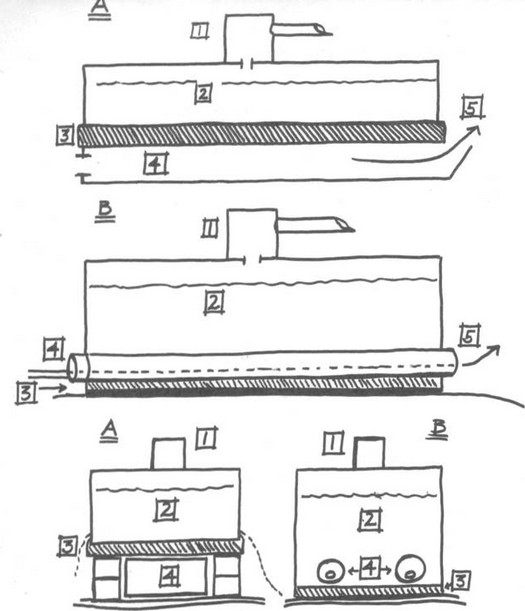

| PLATE 264 In both of the above diagrams: (1) is the cap, (2) the flue at the front of the still through which hot air from the firebox escapes, (3) the bedrock platform built into the furnace wall on which the still rests. As is shown in Diagram A, the platform is not wide enough to extend all the way to the back of the furnace. A large space is left to allow passage of heat from the firebox around the sides of the still. (4) is the firebox. In earlier days, the ends of hardwood logs were used to start the fire, and as the ends burned away, the portions of the logs that extended outside the furnace were gradually fed in to provide constant heat. The arrows in Diagram A show the direction of the heat as it goes around both sides of the still and out the flue. (5) is the furnace wall. It was usually built of natural stone chinked with red clay which would harden through successive burnings. (6) is the still itself—usually made of copper. |

PLATE 265

An abandoned furnace. Often the copper cooker (the "pot")

was removed and hidden in a laurel thicket after each run to prevent its

being stolen before the operator was ready to make another run.

was removed and hidden in a laurel thicket after each run to prevent its

being stolen before the operator was ready to make another run.

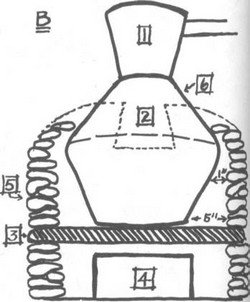

| PLATE 266 - Diagram A illustrates an interesting variation on furnace design which was once fairly popular. Called the "groundhog" or "hog" still, it was unique in that the still sat directly on the ground, and the furnace of mud, clay, and rocks was built up around it with the flue at the back. (1) is the cap, (2) the still, (3) the firebox. The heat was drawn to the flue (4) and circulated around the still in the space left between the furnace and the copper wall of the still. The arrows show the direction of heat. (5) is the back of the furnace—sometimes this was against a bank, and sometimes the furnace hole was dug directly into a bank. The surrounding earth, in the case of the latter design, was extremely effective insulation. When cleverly built, this furnace could also be much easier to hide than the stone furnace which sat right out in the open in most cases. |

A retired practitioner described how the best moonshiners made their forty-fivegallon stills:

Three thin sheets of copper were purchased. The copper had to be absolutely smooth and of good quality. The sheets purchased were approximately thirty inches wide and five feet long. As money was at a premium, every part of the operation had to come out of these three sheets—still, cap, cap arm, slop arm, condenser walls and caps, washers—everything. Planning before cutting, therefore, was essential.

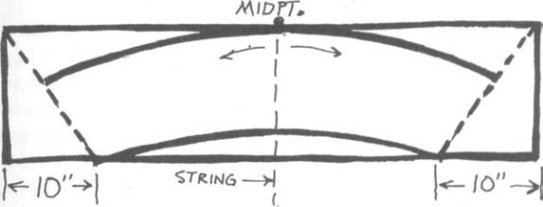

On two sheets of copper, the top and bottom halves of the still were drawn. This was accomplished with the use of a long string which was anchored at a point below the sheet being marked (Plate 267).

PLATE 267

A top arc was drawn so as to be tangent with the mid-point of the top edge of the sheet. The lower arc was drawn so as to intersect the bottom edge of the sheet at points ten inches from each bottom corner.

The third sheet was used for the bottom of the still, the arc from which the cap would be made, the cap head, and the slightly tapered rectangles from which the arms would be rolled.

When this was finished, any blank areas on the sheets were used for drawing small items such as washers. Then everything was cut out. Holes were also cut in the cap, and in the bottom half of the still to make room for the arms which would be attached later.

Next, the two halves of the still were assembled. If the copper being used was too thick to be pulled around by hand, then it was taken to a place in the woods where people would be unlikely to hear what was going on. A large tree was felled in the bottom of a hollow so that the sounds of the construction would go straight up in the air instead of out all over the countryside. The stump of the tree was rounded out to a smooth, concave surface, and the sheet of copper was placed on top.

Next, with a wooden mallet made of dogwood that had been well-seasoned, the copper was beaten until the flat sheet curled around and the two ends touched. One edge was pounded more vigorously than the other so that the sheet would curl unevenly to make the taper. Then holes were punched along the ends of the now-tapered sheet, and brads were inserted to fasten the ends together tightly. The same was done to the other half. Often, to ensure that there would be no leakage at all, these joints would be tin locked.

Now holes were punched along the cape, and the two halves mated and bradded together. The cape edge of the bottom half was crimped slightly so as to fit inside the cape edge of the top half. The arc for the cap was curled in the same manner, and the ends joined as before.

Next the bottom of the still was fastened to the bottom half. (This could also be done before the two halves were mated.) The outside edge of the bottom piece was crimped up so that it would fit outside the wall of the bottom half. The bottom half was set down inside the bottom piece, and the two were fastened together. The tapered slop arm was now rolled and fastened. Its wide end was crimped up. Then it was fed into the still, narrow end first, and out the hole provided for it earlier.

The crimped-up wide end would catch inside the still wall. A washer made of copper slid the length of the arm and fitted snug at the wide end of the arm, but outside the still wall. Holes were punched through and the brads inserted, thus mounting the slop arm firmly to the bottom half of the still. (To taper arm, it was wrapped around tapered wooden pole.)

In like manner, the head of the cap was mounted, the cap arm, and so on until all the parts had been shaped and fastened in their proper places. Then all the joints were sealed with liquid metal so that they would not leak.

The still was now ready to carry to the woods and mate with the furnace. The worm was made there by coiling the pipe around a stump, then slipping it off. The following pages present a portfolio of diagrams which illustrate most of the still varieties we have found. They are arranged in roughly chronological order.

The very first illustration, for example (Plate 268), shows the simplest still of all, and the oldest of the ones we have seen. This is the variety which produced much of the best moonshine ever made.

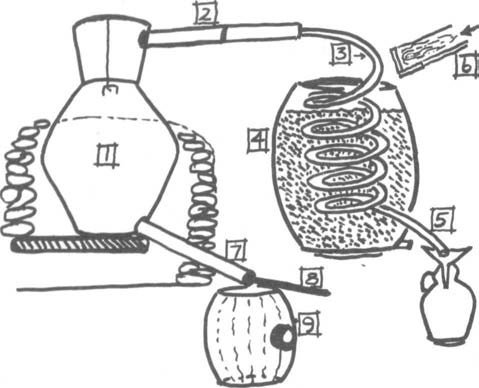

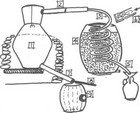

| PLATE

268 Above: (1) the still

(the furnace, bedrock platform, firebox and still cap will be

recognized from a previous diagram). (2)

the cap arm. This copper pipe (often four inches in diameter, but sometimes tapered from six inches at the cap end to four or less at the other) conveys the steam from the still to the copper worm. (3) the worm. This pipe is about three quarters of an inch to an inch in diameter, and is coiled tightly to get maximum length of pipe into minimum space. The steam condenses into liquid in the worm. Sometimes the worm is simply fixed in midair, and the steam cooled by a water jacket which surrounds the pipe and into which fresh, cold water is continually fed, but more often the worm is fixed inside a water tank of some sort—in this case a fifty gallon barrel (4) —through which cold water is constantly circulated. (5) the end of the worm. The alcohol which flows out here is usually strained through hickory coals to remove the fusel oils (barda grease)—thus the funnel above the jug in the diagram at the end of the worm. (6) the pipe, or trough from the cold water source—usually a mountain stream. (7) the slop arm. The spent beer is drained out this copper pipe (which passes directly through the furnace wall) after each run. (8) the plug stick. This is usually a hickory or oak limb with a wad of rags attached firmly to the end to keep the beer from draining out during a run. (9) the container for the slop (spent beer). |

| PLATE

269 Mickey Justice holds a section of a wooden water

trough found at the site of one of the earliest and most famous stills

in Rabun County. The trough carried fresh water from a spring far up the hill to the still's condenser. |

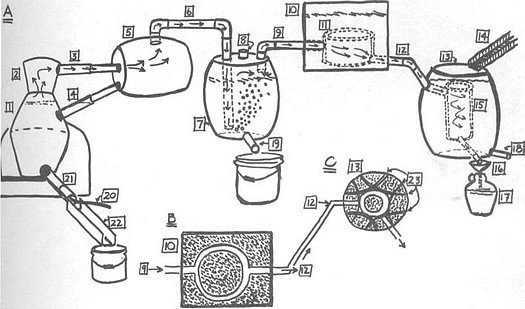

PLATE 270 - BLOCKADE STILL

| PLATE 270 Refined to the ultimate, this version—Diagram A—of the Blockade Still works as follows: The steam (arrows) from the beer boiling in the still (1) moves into the cap (2), through the cap arm (3), and into the dry or "relay" barrel (5). Beer which bubbles over or "pukes" into the relay barrel is returned to the still via the relay arm (4). From this barrel (usually a fifty-gallon one which is mounted so that it slants slightly back toward the still), the steam moves into the long thump rod (6) which carries it into the bottom of the fifty-gallon thump barrel (7) and releases it to bubble up through the fresh beer, which was placed there earlier via inlet (8)—now closed to keep the steam enclosed in the system. The beer in this barrel is drained after each run and replaced with fresh beer before the next. Picked up again at the top by the short thump rod (9), the steam moves into the heater box or "pre-heater" (10) which is also filled with fresh beer. Here the steam is not set loose, however, but is forced through a double-walled ring (11) that stands about nine inches high, is thirty-four to forty inches in diameter, and mounted so that it stands about a half inch off the floor of the heater box. The top and bottom of the ring are sealed so that the steam cannot escape. Heat from the steam is transferred to this cool, fresh beer thus heating it to make it ready for the next run when it will be transferred into the drained still via a wooden trough connecting the two (not shown here). The steam then moves via another connecting rod (12) into the flake stand (13) and into the condenser (15)—in this case another double-walled ring, higher and narrower than the previous one. The steam is condensed in this'ring by the cold water flowing into the flake stand from (14) and exiting by outlet (18). As the steam is condensed into alcohol, it flows through a strainer and funnel (16) into the container (17). |

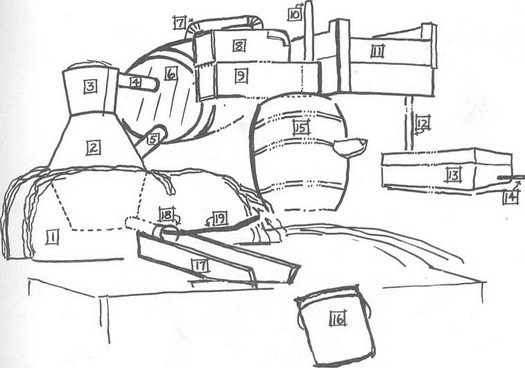

PLATE 271 -

Blockade Moonshine Still System

| The

still from which this diagram was drawn was a "fifty-gallon rig." The still and all three barrels each had a fifty-gallon capacity. The heater box was twenty-eight inches long, twenty-eight inches wide, and stood twenty-four inches high. The relay barrel and the heater box were both tilted slightly in the direction of the still-cooker for proper drainage. Diagram B shows the heater box from the top, sliced in half. The dots represent beer; the steam is represented by arrows. Diagram C shows the flake stand from the top. In this case the condenser was held in place in the center of the barrel by twigs (23) which were cut green, then bent and wedged against its sides. The dots represent water. At the end of each run, the plug stick (20) is pushed in, thus releasing the slop or "pot-tail" which flows through the tilted slop arm (21) and trough (22) into a bucket. The spent beer from the thump barrel (faints) is also drained and replaced. The plug stick is replaced, the cap removed, the still filled with hot beer from the heater box, the cap is replaced, the heater box is filled with fresh cold beer again, and the process is begun all over. PLATES 271, 272 The still shown in Plate 271 is another of the highly refined Blockade variety. In this case, however, rather than being stretched out for convenience of illustration, the diagram's shapes match those of Plate 271 so that you can decipher the photograph itself. It is basically the same as the previous operation, but in this case it is possible to see the trough which connects the heater box with the still. Part (8) is hinged to part (9), and when the operator is ready to move the beer, he takes the cap off the still, swings (8) down so that it is in line with its lower half, pulls the gate up via the gate handle (10), and lets the beer flow. In the diagram, the log supports which hold up various parts of the operation and which can be seen in the photograph, are not shown as they would create too much confusion. Instead, they are indicated by dotted lines in those places where they pass in front of a portion of the still. The flake stand, in this case, holds not the condenser which was used in the still on the previous pages, but a radiator from a Chevrolet truck. The radiator is just as effective a condenser but often not quite as healthy. The numbers on the diagram refer to the following parts of the still shown: 1) the furnace 2) the still 3) the cap 4) the cap arm 5) the relay arm 6) the relay, or dry barrel 7) the long thump rod—its connection with (15) is hidden 8) top half of trough from heater 9) bottom half of trough 10) handle for heater box gate 11) heater box 12) copper connecting rod 13) flake stand—water filled 14) outlet from condensing unit 15) thumper, or thump barrel 16) bucket for slop, or "pot-tail" 17) slop trough 18) slop arm from still 19) handle of plug stick  |

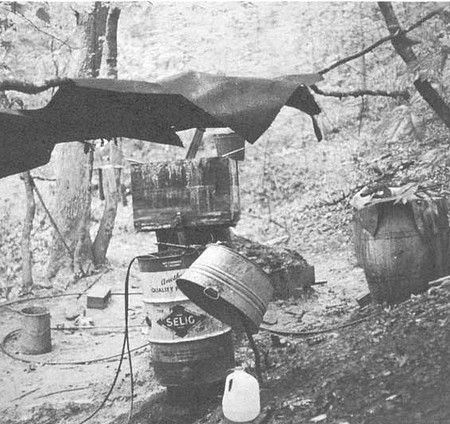

| PLATE 273 The beer in this cooker is being heated prior to sealing on the cap. The swab stick resting in the cooker is used to stir the beer while it is heating to keep it from sticking to the sides and burning. Both this and the next three photographs were all taken at the same operation. |

| PLATE 274 The thump barrel and heater box. The drain pipe, when lowered, carries warm, fresh beer from the heater box to the cooker, the top of which is visible in the foreground. |

| PLATE 275 The heater box from the other side, showing the connection between the heater box and the condenser which is mounted in the metal drum. |

| PLATE

276 The whole operation from the heater box, condenser end. The wooden barrels on the right are filled with fermenting mash. The furnace is hidden behind the heater box. The plastic gallon milk jar in the foreground is often used in place of glass jars for the finished product. |

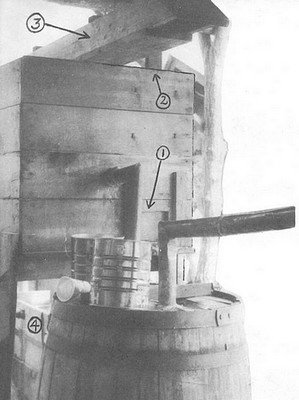

| PLATE 277 This page reveals a heater box and a thump barrel in more detail. The barrel in the foreground of the photograph is the thumper. The pipe extending in the foreground is the long thump rod coming from the cap of the still. (This particular still did not have a dry or relay barrel). The large wooden box behind the thumper is the heater box. Arrow I points to the outlet which is blocked by the gate behind it. Arrow 2 points to the handle of this gate. Arrow 3 points to the wooden trough which is mounted into place when the operator is ready to transfer his preheated beer to the still for a new run. In the background, behind the thump barrel (bearing the number 4) can be seen the corner of the flake stand. |

| PLATE

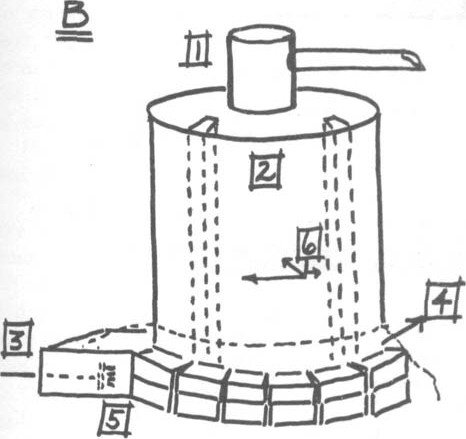

278 (1) is the cap—usually

a fifty-gallon barrel. (2) is a huge barrel (the still) which sits right on the ground. It has, in this case, a capacity of five hundred gallons. The sides are made of huge sheets of aluminum or copper, and both the top and bottom are made of plywood. There are three 2 by 4 supports inside the walls of the still which help support its great size (6). (3) is the firebox. The source of heat, in this case, is a huge gas burner mounted so that the flames point toward the still. Heat is drawn in, around the lower walls of the still, and out the flue (4). (5) is the furnace which in this case is a double row of concrete blocks sealed over (dotted line) with clay, or some other form of tight insulation. Space, of course, is left between the inside wall of the blocks and the outside bottom wall of the still for the passage of heat. The cap arm connects to a large thump barrel which connects directly with the flake stand. There was no heater box in this particular model. It is possible, by the way, to use a fifty-gallon barrel as the housing for the gas jets (3). It would be turned on its side with its end toward the still, and sealed to the concrete-block wall of the furnace with the insulating rocks, mud, and concrete. Those who use them say that the groundhog stills are much hotter than the other varieties, and thus make better stills. |

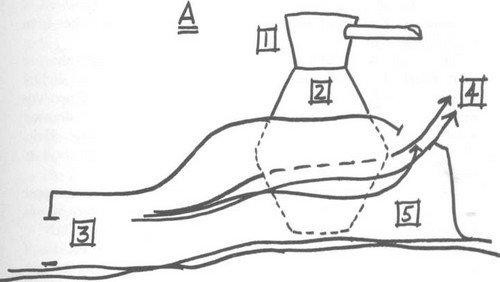

| PLATE

279 These diagrams illustrate perhaps the simplest still

of them all—the "dead man" or "flat moonshine still." In all cases

(Diagrams A and B) : (1) is the cap, (2)

the still itself—a rectangular box, (3)

the bottom of the box (the diagonally shaded area), (4)

the firebox or source of heat, and (5)

the flue. There are several differences between them, however, that

make them interesting. In A, the cap is a twenty-five-gallon barrel, and in B, a fifty-gallon one. The firebox in A is simply a channel cut into the earth. The still sits on the ground directly over this channel. A hole is left at the back to serve as the flue. In B, however, two 7 inch pipes sit inside the still box, surrounded by beer, with their ends protruding out both ends of the box. A long gas line is fed into each of these pipes, and its top surface is perforated in the manner of gas burners on stoves. This design supplies heat directly to the beer thus making a faster operation. In A, the still stands two feet high, and six to eight feet long. A thin sheet of copper lines the outside of the bottom, and rises up two to three inches all around the sides. The rest of the box is made of wood. In B, the box is made of two 4-foot-square wooden boxes. They are mounted side to side, and the common wall is removed leaving a box four feet high, four feet wide, and eight feet long. The bottom is lined with copper as before. Diagram A at the bottom shows how concrete blocks could be used in lieu of digging a trench in the ground. The dotted lines represent the insulation (mud, rocks, cement, etc.). |

It was also the most time-consuming of all the operations, and yielded the smallest return for the time involved. All the beer was run through, a stillful at a time, and the results of each run ("singlings") saved at the other end. When all the beer had been run through once, the still was thoroughly cleaned, and then all the singlings placed into the still at one time. Then the stillful of singlings was run through.

The result was the doublings, or good whiskey. It was also called "doubled and twisted" whiskey, the first because it was double strength, and the second, because it twisted slightly as it came out of the worm. Using this rig, a man could get about two gallons of whiskey per bushel of corn, or a final yield of about twelve gallons after proofing.

By way of contrast, there are operations running today which yield as much as three hundred gallons per run—a far cry from the old days.

The two previous stills show what happened as moonshiners got more and more impatient with the slowness of the first operation described.

Perhaps the most revolutionary addition was the thump barrel. Steam bubbling up through the fresh beer in this barrel was automatically doubled thus removing forever the necessity of saving the singlings and. running them through again to double their strength.

The still in Plate 278 illustrates effectively what happens as man's desire for quantity overtakes his desire for quality. The yield from this still is immense; the quality, questionable. A truck radiator serves as the condenser.

The dead man still in Plate 279 is a purely modern variety with a tremendous yield. The beer, rather than being made in separate boxes, can be made right in the still in this case. Twenty bags of sugar are used. One run can produce forty-five cases. There are six gallons in each case, so the total yield is 270 gallons. Early this year, the whiskey from this still was commanding $30 to $35 a case from the bootlegger's hauler. If the operator had had to haul it to the bootlegger, he would have added $10 more to the final price of each case.

The operation of a steamer still similar to the one in Plate 280 was described thus by one operator: "It takes four men—a chief, a helper-pumper, and two haulers. We make our beer in six 4' by 8' boxes, and use two thousand pounds of sugar for every load. If we don't get twelve cases out of every box, something's wrong. And that's only seventy-two cases a day. That's not bad, but when I was running eight boxes I got ninety-six cases a day. And sometimes I could sell it for $60 a case. Not now. Price goes up and down—it depends.

"We use what we call 'mule feed' for malt, and we add beading oil to make it bead good. We use a radiator out of a Dodge truck in th' flake stand, cleaned out good, of course. "I just want to move th'stuff out—get it to th'bootlegger quick as it's made. That's why I use haulers. I admit it's not good liquor. It'll give you a headache. But it won't hurt you. I've drunk it myself before."

Several things make a steamer still difficult. One is the amount of beer that must be on hand to begin with. From each 190 gallons in the Hodges Barrel, the yield will be approximately seven cases. Thus, in order to run off the ninety or more cases that can be run in a day, the main barrel has to be emptied and refilled about ten times.

One man we talked to accomplished this with a pump and hose apparatus that he had rigged up. Contrast this with the old method of dipping the beer into the still with five gallon buckets and one can see how much things have changed. It still takes time, however, to prepare the beer. Thus a still like this one must lie unused for days at a time waiting for the beer to be ready to run.

Sugar presents another problem. Since anything over a hundred pounds must be signed for, sugar has to be bootlegged just like the whiskey.

In addition, the very size of the operation makes it more dangerous to run. Every effort is made to minimize the risk.

One man, for example, told us that he never uses pegs in the outlet holes of his barrels. He has converted everything to valves. The reason: "Men who use pegs get in th' habit of hitting them three times whenever they're putting them back in th' holes. They hit that peg soft th' first time, a little harder th' next time, and on th' third time they really whack it. You can hear those three licks on th' thumper peg for miles."

Once two men were fixing a leak in th' side of their still. One of th' men was inside th' still, crouched down, giving support from th' inside; th' other was outside with a hammer pounding away at th' patch he was adding. Suddenly th' man on th' outside saw th' law headed straight for him. Without a word to his partner inside th' still, he turned and fled into th' woods.

Th' federal man came up to th' still. Unaware that anyone was inside it, he took th' pick with which he demolished stills and gave it a terrible whack, piercing the side. "Now you've ruined it," th' man on th' inside screamed in anger.

How the Best of the Best Moonshine was Made - How to Make Traditional Moonshine

As told by the men who made it.For this section, two men who are reputed to have made some of the best moonshine to come out of Georgia tell exactly how they did it. The process for making "pure corn" is the base of the discussion. Use of sugar in a run to increase the yield is also included, but in parentheses, as the addition of sugar would not allow the mixture to be labeled as pure corn whiskey. Use of a thump barrel is included for it does not diminish the quality of the product, and thump barrels were used during the old days.

Both of the men are now retired, and watch production today with increasing disdain. Here's how they made moonshine, from beginning to end, using a fifty-gallon still and seven 50-gallon barrels:

1. Go to the woods and find a good place. Make a mudhole which contains plenty of good, thick red clay for use in the furnace. Also construct any water lines needed for the flake stand.

2. Choose the corn. Do not use a hybrid or yellow corn. Use a good, fresh, pure white corn like Holcomb Prolific which will produce about three quarts of whiskey per bushel. Inferior brands will only produce about two and a half quarts per bushel. Get nine and a half bushels.

3. Put at least a bushel and a half of corn (but not more than two) aside to sprout. In winter, put this corn in a barrel or tub, add warm water, and leave it for twenty-four hours. Then drain it and move it to the sprouting tub. Cover it with pretty warm water, leave it for fifteen minutes, and drain the water off.

Put the tub close to a stove, and turn the cold side to the stove at least once a day. Each day add warm water again, leave it for fifteen minutes, and drain it off again leaving the tub close to the stove. Also transfer the corn on the bottom of the tub to the top of the tub at least once a day to make sure it all gets the same amount of heat.

You should have good malt in four or five days with shoots about two inches long, and good roots.

In summer, simply put the corn to be sprouted out in the sun in two sacks. Sprinkle warm water over them once a day, and flip the sacks over. It is also possible to sprout the corn in sacks under either sawdust or mule manure—both hold heat well.

Be careful, however, not to let the corn get too hot or it will go slick. When it starts getting too hot, stir it up and give it air to cool it.

4. The day before the sprouted corn is ready, take the remaining eight bushels of corn to the miller to be ground up. Don't let him crush the corn or you'll have some heavy material left that will sink to the bottom of the still and burn. Make sure he grinds it all up fine. Take this meal to the woods.

The last three or four days should have been spent building the furnace and installing the still. It should be ready to work now. Build a fire under the still. Fill it nearly full with water, and stir in a half-bushel of corn meal. When it comes to a boil, let it bubble for thirty-five to forty minutes. Cook it well or it will puke too much when cooking later.

When it has cooked sufficiently, bring one of the barrels over, put it under the slop arm of the still, push in the plug stick, and let the contents of the still fill the barrel. Add a gallon of yet uncooked meal and let the hot contents of the barrel cook it alone. Make sure it is stirred in well. Move the barrel aside, and repeat the whole process until all the meal is cooked, and all seven barrels are filled. Return home.

5. The next day, get the sprouted corn (malt) ground up at the mill and take it to the woods. Use a miller who knows you and will keep your activities secret. He will take no toll for grinding your malt. He'll take his toll out later when you are grinding straight corn again. You can also use a sausage mill.

In the woods, thin out the mash you made yesterday. This is done by standing the mash stick upright in each barrel. Add water and stir it in until the mash stick falls over against the side easily of its own weight.

When all are thinned, add a gallon of malt to each barrel and stir it in. At the same time, add a double handful of raw rye to each barrel, sprinkling it around over the top. This helps to make the cap, helps the mixture begin working, and helps the final product hold a good bead. (If using sugar, add ten pounds to each barrel at the same time you add the malt.) Cover the barrels. If they get rained into, your work is ruined. Return home.

6. The next day, the mixtures should be working. If one or two of them aren't, then mix them back and forth with those that are, using a dipper. You want them all to be working at the same time so that they'll all be ready to run at the same time. This liquid is now known as beer. Return home.

7. The next day, return to the site and stir up the mixture in each of the barrels to speed up their working. Home again.

8. About two days later, check again. At the same time, gather the wood you will need, bring in kegs, fruit jars, and whatever else you may need. (On this fourth day, if you're using sugar, add a half gallon of malt to each barrel and thirty-five to forty pounds of sugar to each barrel. Stir in and let the mixture work for five more days.)

9. If you are not using sugar, then the whole mixture should be ready to run on the fifth day of its working. (With sugar, it takes about nine or ten days.) You can tell when it's ready to run by studying the cap that has formed over the beer. Sometimes this cap will be two inches thick. Sometimes it will only be a half inch thick, and sometimes it will just be suds and blubber, called a "blossom cap." All of these are fine.

When the cap is nearly gone, or only a few remnants are left scattered over the top, the mixture is ready to run. The alcohol has eaten the cap off the beer. Don't wait to run it at this point or the mixture will turn to vinegar, and the vinegar will eat the alcohol thus ruining your beer. It is better to run the whole thing a day early than a day late—you'll still get mild, good whiskey.

Appearance of "dog heads" also indicates that it's ready to run. [Note—one variation on the above process was also popular. Two bushels of mash were put in each fifty-gallon barrel, and cold water added. No cooking was used. This mixture would sour in three or four days and produce a crust. This would be broken up, stirred in, and the mixture left for another two or three days until it had soured again. Then a gallon and a half of malt was added to each barrel, and the mixture allowed to work another week. At this point, it was ready to run in the same manner as the other we have been describing.]

10. Now all connections on the still are sealed up with a stiff rye paste save for the cap and cap arm. The plug stick is inserted through the top of the still, handle first, and the handle pulled out through the slop arm until the ball of rags at the other end jams the opening. Fill the still almost to the top (leave about three gallons off for expansion due to heat) with the beer. Put ten gallons of beer in the thump barrel.

Build up the fire underneath, and as the beer heats, stir it constantly with the swab stick to keep it from sticking to the bottom and sides of the still. Keep this up until it has come to a rolling boil and can thus keep itself stirred. Then paste on the cap and cap arm using the rye dough.

11. Chunk the fire easy, starting slowly, and gradually building it up in intensity. About fifteen minutes after the beer starts boiling in the still, the steam will hit the cold beer in the thump barrel and start it bubbling and thumping.

On cold days, this thumping can be heard for several hundred yards through the woods. When the thumping quiets, the beer is boiling smoothly in the still and doing fine. Place a container under the end of the condenser. A funnel should be inserted in the container which is lined with a clean, fine white cloth on the bottom, a yarn cloth on top of that, and a double handful of washed hickory coals on top of that. The coals remove the "hardy grease" (it shows up as an oil slick on top of the whiskey if not drained off) which can make one very ill.

12. When the thumping stops, the whiskey starts. A gush or two of steam will precede it at the condenser end. This will be followed by a strong surge of liquid which quickly subsides to a trickle. On the second surge, "she's coming for good," as one man said. Begin catching the alcohol on the second surge. (If it is being made with sugar, this first run will not hold a bead. Save it anyway. Keep running the still as long as there is any taste of alcohol in the liquid being produced.

Then drain the thump barrel. Add the results of the first run— about ten gallons of backings. Then drain the still through the slop arm and fill it again with beer as before.

13. On the second run through, you'll have good whiskey because the steam has gone through the backings in the thumper. It will be double strength. Keep checking it with the proof vial, catching it as it comes out of the condenser, thumping it in the palm of your hand, and watching the bubbles. When it's dead, pull the container away.

You should have two to three gallons of whiskey, the bead on which will be half under the liquid and half over it. (If you're running sugar whiskey, the results from the first run on will be whiskey, and the bead will be two-thirds under the surface and one-third over it.) Catch the remainder of the second run in another container. These are the new backings for the third run.

Another way to tell whether or not the whiskey is still strong enough to catch in the container of good stuff is by taking some of the alcohol, dashing it on the hot still cap, and holding a match to the resulting steam. If it burns, keep it running.

14. From the second running, you should have two or three gallons of good whiskey and seven or eight gallons of backings. Drain the faints out of the thumper and "let them hit the ground and run away." They are no good for anything. Add the new backings to the thumper.

Drain the still, fill it again with fresh beer, and run it the third time. This time, since there are fewer backings, you'll get less liquor, but more backings for the fourth run. On the fourth run, you'll get more liquor because you have more backings, but you'll also get fewer backings for the fifth run; and so on. The yield will vary up and down with each stillful.

Keep running until all the beer has been used up. Without a thumper, all the backings would have been saved, and all run through the still together on the last run.

15. After about seven runs, the net result will be seven to ten gallons of pure corn (unsugared) whiskey, for an average of about a gallon to a gallon and a half per bushel of corn. (With sugar, the result should be about six gallons to the bushel.)

These are called the "high shots." They are about 200 proof and must be cut to be drinkable. To cut, either add about one-third backings from the last run, or water. Many prefer water.

Add the liquid you are cutting the alcohol with until it holds a good steady bead in the proof vial. If the bead will hold steady after three good thumps in the palm of your hand, then it will stand any amount of jolting and bumping in shipment.

From nine gallons of high shots, you should get about twelve gallons of fine whiskey.

Other Moonshining Tips and Hints:

1. If a wood fuel is being used, ash is the best of all. It gives a good, steady heat, and little smoke. Also good are hickory and mountain oak.

2. Always use copper. Beer doesn't stick to it so badly, and there

3. Never let the whiskey run too fast. Always keep it cold while it's running. If it is kept as cold as the water it is being condensed by, it will remain smooth and mild and not harsh to the taste. About sixty degrees is normal.

4. Use the best water available (many prefer streams running west off the north side of a hill). The water can make a difference of several gallons in the final yield.

5. Everything must be kept spotless. The copper inside the still should shine like gold. Barrels (or boxes) too must be kept clean. Smoke them out after each use with several handfuls of corn meal bran set afire.

6. Add three or four drops of rye flavoring to each gallon of whiskey to give it a yellow tint and a distinct rye flavor.

7. The place to make the whiskey is in the boxes. If it's not right there, no amount of boiling and cooking can save it.

How Good Whiskey is Being Ruined

1. Stills are often made of sheet iron or valley tin instead of copper. These metals often burn the beer and give it a strange taste.2. The beer is often run too early before it has a chance to sour properly.

3. The whiskey is sometimes condensed in a straight worm which does not let it slow down enough to cool off properly. This gives it a harsh, hot taste.

4. Often whiskey is scorched because it is not watched properly, not stirred while heating, or because the fire under the still is too hot.

5. If whiskey is not strained properly, it will contain elements that can make one violently ill.

6. Radiators used as condensers are extremely dangerous. They can never be cleaned out completely, and the end result is sometimes whiskey that can cause lead poisoning.

7. Potash is sometimes used to "fake" a high bead. This is the same material soap is made out of, and it can be poisonous.

8. Sometimes potash and ground up Irish potatoes are added to the malt to make it work off quicker and yield more.

9. Often vessels are left dirty, and produce "popskull" liquor.

10. Instead of pure corn malt, some use yeast.

11. Instead of pure corn meal, some use "wheat shorts" so it won't stick to the still.

12. Many cut the final product to 60—70 proof and add beading oil to fake quality and high proof.

13. It is rumored that some people set batteries down in the mash boxes to make it work more quickly; but another we talked to hinted that that might just have been a rumor put out by federal agents to hurt the sale of whiskey. We could get nothing concrete on this one way or another.

14. One of our contacts knows a man who uses a groundhog still which he fills two-thirds full of water which he then heats. Then he adds fifty pounds of wheat bran, four 100-pound sacks of sugar, and two cans of yeast. That's it. No souring—nothing. Apparently it makes "pretty" whiskey which holds a good bead, but has a funny "whang" flavor.

The biggest problem, of course, is as we have hinted several times before—the desire for quantity rather than quality. One retired moonshiner said, "When I was working for th' forest service and saw th' filth and th' nature of most of th' stills in th' woods today, th' prouder I was that I quit drinkin' th' stuff. I don't see how more people don't get killed."

Another claimed that he had often had people who make whiskey themselves come to him to buy the liquor they were going to drink. They were afraid to drink their own.

It apparently is not that difficult to get away with making bad whiskey, because most of it is sold through bootleggers who themselves don't know where it came from. In addition, much of it is shipped to the poorer districts of some of the bigger cities, and the people who buy it there have no means of finding out who made it. Thus the operator of the still is reasonably safe, rarely having to pay for his sloppiness.

He earns little respect among his neighbors, however. As one said, "A man ought to be put in a chain gang with a ball tied to him if he uses potash to make whiskey. 'Bout all you can call that is low-down meanness. He ain't makin' it t'drink himself, and he ain't makin' it fit for anyone else to drink neither."

Marketing Moonshine: How to Get Rid of the Final Product

In the early days of moonshining, it was a relatively easy matter to dispose of the whiskey. In the first place, there wasn't that much of it. Also, most of the neighbors knew who in the area was busy in that pursuit, and so they knew where to go when they needed to make a purchase.The moonshiner knew his neighbors, usually knew who could be trusted, and so everything worked out well. There were no big business overtones, no high pressure sales, just quiet, behind-the scenes, low-key transactions during which no one asked unnecessary questions.

Things began to change, however, during Prohibition. One man we talked to could remember huge trailer trucks coming down off his mountain loaded with thousands of gallons of whiskey and headed north. The operation has remained the realm of the relatively big operators.

The great majority of the whiskey produced is distributed through bootleggers who buy it directly from the makers. They usually hire their own haulers so that they don't have to pay the owner of the still for moving it for them. The bootlegger usually gets it from his haulers, waters it down, puts it in jars, and then distributes it to his regular customers, making deliveries to regular customers on a regular schedule. Sometimes these customers are store owners who sell it again to their customers.

It is a tight, shadowy operation, sometimes run by men who are among the most highly respected citizens in the community. For these men, their double life also pays off in a handsome double income. Sometimes bootleggers have ingenious ways of hiding their wares while waiting for them to be disposed of.

One we heard of has a clothesline strung across a lake in his backyard. The line is circular, and runs on a pulley system. The bottom half of the line contains clips which are, in turn, hooked to the tops of fruit jars that are full of whiskey. These jars remain submerged under the lake all the time. Once customers show up, the correct number of jars is pulled up and old.

Another operator, this one relatively small, kept the product he was selling in the sleeves of the clothing which hung in his closet. The men who run the real risks, however, are the haulers, who have perfected hundreds of ways of moving whiskey.

Some of these:

1. One man hauled only on Sundays. On these days, he would have eight cases concealed in the trunk, two under the hood, and his wife and little girl in the car with him. The car was "shocked up" so that no excess weight showed, and he rode around enough so that no one suspected that he was in a hurry to get anywhere. He was never caught.

2. Another filled the bed of his pickup truck two cases high, and then put a black plywood form on top so that at night it looked empty. The truck held twenty cases.

3. Others have big trucks with false beds in which they can fit a single layer of cases.

4. Some haul, even today, in dump trucks or cabbage trucks which have such high sides that they can't be seen into from the road. If they are afraid of getting caught, they sometimes stack all the cases of moonshine in the center of the bed and cover it completely top and sides with ears of corn.